Smartphones began life as telephones. Today they are portable computers, classrooms, marketplaces and paychecks in the pockets of millions. For Africa’s young people — a cohort of roughly 400 million — that tiny rectangle of glass and metal is more than convenience: it is a gateway to schooling, skilled work and economic independence.

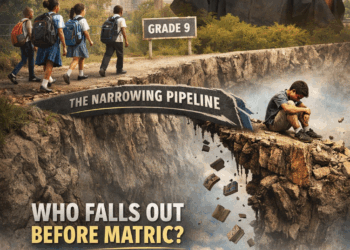

The numbers are stark and unavoidable. Each year 10–12 million young Africans enter the labour market and compete for approximately 3 million formal jobs. For the vast majority who don’t win one of those positions, the smartphone is often the difference between being shut out and being plugged into global opportunity. Through e-hailing apps, mobile money wallets, online marketplaces and remote freelancing platforms, digital access converts geographical limits into market reach.

A changing jobs landscape

The job market itself is being reshaped by digital transformation. Traditional, on-site, salaried roles are giving way to gig work, freelancing, remote employment and micro-entrepreneurship. These new income pathways are easily accessible — if you have the device and connectivity to reach them.

Technology is also creating whole new occupational categories. Emerging fields such as generative AI, cybersecurity, blockchain and cloud computing require digitally fluent entrants. Forecasts suggest that over the next five years an estimated 230 million digital jobs will be created in sub-Saharan Africa — a figure that points to the scale of demand for digitally skilled labour and the potential for mobile devices to be the entry ticket.

A credit gap that shuts youth out

Yet access is not only about signal strength and apps. A practical and often overlooked barrier is access to finance. Many young Africans — and South Africans in particular — lack the formal credit histories that traditional lending systems use to determine eligibility for loans and contract purchases. In South Africa, of the 6.7 million individuals aged 18–24, only around one million are credit active. This is not necessarily a sign of financial instability; it is frequently a sign that the system simply isn’t designed for first-time earners entering the formal economy.

That gap matters because smartphones are not free. For a young person trying to study online, run a small e-commerce venture, or access remote work, a reliable device is an essential tool. When credit systems require payslips, long bank histories or collateral, many young people are left to buy lower-quality phones, rely on shared devices, or forego access entirely — and with that, the opportunities that flow from it.

PayJoy: credit-building, not gatekeeping

This is the context in which PayJoy began operating in South Africa: to help close the divide between aspiration and access. Our approach is designed for people at the start of their economic journey — those without years of payslips or entrenched credit records — by offering responsible device access without long-term commitments and with the opportunity to build credit.

PayJoy’s application process does not hinge on traditional documents alone. By combining alternative data points and a flexible repayment structure, the platform lets young people obtain smartphones and simultaneously begin constructing a formal credit history. The early signs are encouraging: more than 14% of PayJoy’s customers in South Africa are under the age of 27, indicating a real appetite among youth for pathways to device ownership that also protect them from predatory credit.

Why this matters for education and employment

A smartphone in hand transforms how a young person learns and works. It delivers access to online courses and micro-credentials, to global job listings and remote gigs, to small-business tools and payment rails that enable entrepreneurship. It also lowers the friction for entry into high-growth tech sectors: learning to code, contributing to cloud projects, or participating in cybersecurity training is possible from a basic smartphone today and becomes more powerful with incremental upgrades.

But beyond theory, there is a human story here. When a young person can reliably access learning, market themselves online, or accept payments digitally, they shift from passive job-seeker to value-creator. That ripple effect benefits families, communities and — eventually — national economies.

A call for systems that include first-time entrants

The path forward is twofold. First, policymakers, educators and employers must continue to recognise and support digital pathways to learning and work — from subsidised connectivity and digital curricula to apprenticeship and remote-work incentives. Second, the financial sector must evolve to accommodate young, credit-naïve entrants: alternative underwriting, credit-building products and consumer protections that prevent debt traps are essential.

At PayJoy, we see our role as practical and catalytic: to make device ownership responsible and attainable, and to provide a route for the young to build a formal credit profile as they begin to earn. When smartphones are responsibly within reach, education, employment and entrepreneurship become realistic options rather than distant possibilities.

Conclusion: phones as instruments of inclusion

Africa’s demographic dividend is not automatic; it must be unlocked. Smartphones are a tool of enormous potential — but only if the finance architecture, education systems and employer mindsets evolve at pace with technology. For the continent’s 400 million young people, that change will determine whether they are spectators to a digital economy or its makers.

If we get this right — by widening access, building fair credit pathways and scaling digital skills — the smartphone will stand as one of the most powerful instruments of inclusion this century: a small device whose returns ripple into livelihoods, communities and national growth.