South Africa’s latest matric results delivered a historic 88% pass rate — a milestone that deserves recognition. It reflects system resilience, improved coordination, and the sustained effort of teachers, learners, families and policymakers working under often difficult circumstances.

For social investors, however, this moment is not only about celebration. It is also a moment for deeper interrogation: to look beneath the headline number, to understand where progress is genuine, where inequality remains entrenched, and where targeted investment can unlock the greatest long-term impact.

A System Shaped by History — Moving Forward Unevenly

South Africa’s education system continues to operate within the long shadow of an intentionally unequal past. Against this backdrop, the progress made since democracy is substantial and too often under-acknowledged. Educational outcomes for black African and coloured learners today far exceed those of 30 years ago, reflecting decades of reform, investment and determination.

But progress should not be mistaken for sufficiency. The system still falls short of delivering high-quality education equitably across the full cradle-to-career continuum.

At the early primary level, the gains are particularly striking. Around 94% of 10- and 11-year-olds now pass Grade 3, up from approximately 78% two decades ago. Yet pass rates alone are not a proxy for meaningful learning. Only about three-quarters of learners can read for meaning at this stage — a gap with profound consequences for every subject that follows.

These quality disparities are most visible in the contrast between no-fee Quintile 1–3 schools, often operating with minimal infrastructure, and well-resourced schools offering libraries, laboratories, astro turfs and even Olympic-size pools. These differences mirror broader socio-economic divides that education alone cannot resolve — but which it can either entrench or disrupt.

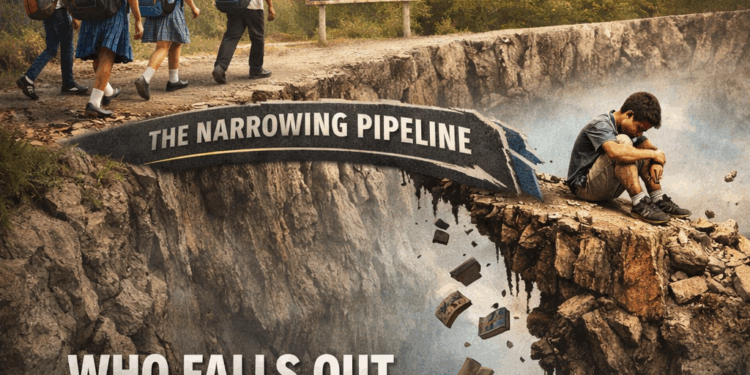

The Narrowing Pipeline

From a systems perspective, social investors focus on educational pressure points — stages where learners are most likely to fall behind or exit the system entirely. Grade 3 and Grade 9 consistently emerge as the most critical.

By Grade 9, pass rates decline to around 75–76% among 16-year-olds, signalling the onset of significant learner attrition. The downstream numbers are sobering. Of the roughly 1.2 million children born each year who enter Grade 1, only about 650 000 ultimately reach and pass matric. Of those, approximately 250 000 pass mathematics.

Beyond school, the pipeline narrows even further. About 340 000 learners enter university annually, and only around 200 000 graduate. As a result, just 15–16% of South African adults hold a post-school qualification, well below the National Development Plan’s target of 25%.

Why Early Investment Delivers the Greatest Return

At Tshikululu Social Investments, growing evidence points to early childhood development (ECD) as the highest-return investment opportunity in the education system. Interventions from conception through the first 1 000 days — including quality crèche provision and caregiver support — have lifelong effects on cognitive development, curiosity and learning capacity.

The foundation phase (Grades 1–3) is equally decisive. Improving reading for meaning during these years can fundamentally reshape a learner’s entire educational trajectory. Many social investors are now working toward an aspirational shift: moving from one in four learners reading adequately by Grade 4 to three in four. Such a change would reverberate across the entire system.

Children who develop a love of reading early are far more likely to engage meaningfully with mathematics, science and biology later — skills the South African economy urgently needs.

Matric Momentum — and Why Quality Still Matters

At the senior end of the system, there is genuine cause for cautious optimism. The matric engine is humming. Despite periodic disruptions, including isolated paper leaks, the system has demonstrated growing resilience and improving coordination.

The 88% pass rate reflects this momentum and sets a strong benchmark for future cohorts. For social investors, however, attention extends beyond headline pass rates to the quality of outcomes — particularly pure mathematics passes and bachelor-level passes, which open pathways into STEM fields at universities and TVET colleges.

Encouragingly, steady improvements over the past three years suggest that progress in these areas is gaining traction.

Strategic Leverage Points for Social Investors

The education landscape offers no shortage of intervention opportunities: foundation-phase literacy, wraparound university bursaries, and post-school training aligned with B-BBEE priorities all remain vital.

Increasingly, however, Grade 9 is emerging as a strategic leverage point with outsized impact.

Strengthening outcomes at this level can keep more learners in the system, redirect them into viable vocational pathways, and reduce the sharp drop-off that currently occurs before matric. Significant work remains to improve the quality and appeal of these pathways — including expanded access to TVET colleges, skilled trades such as plumbing, electrical work and mechanical engineering, and community colleges offering marketable skills for the modern economy.

Unlike countries such as Germany, South Africa remains heavily skewed toward university qualifications, often at the expense of vocational training. By raising the floor while still pursuing excellence, social investors have an opportunity to help rebalance the system — narrowing inequality, strengthening the skills pipeline, and accelerating inclusive economic development.

The 88% pass rate is real progress. The challenge — and the opportunity — lies in ensuring that fewer learners fall out long before they ever reach matric.