The week before World Food Day, the future arrived with a charger cable and a communal pot of ideas.

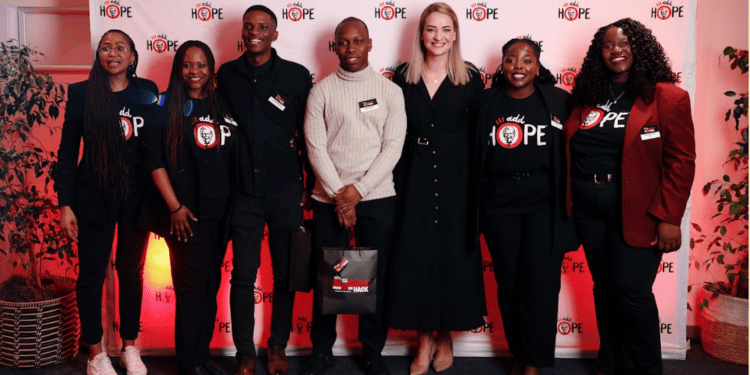

Sixty Gen Z coders, designers and social-entrepreneurs converged at the University of Johannesburg for The Biggest Hunger Hack — an accelerated, high-stakes experiment in civic tech hosted by KFC Africa to re-engineer its flagship anti-hunger programme, Add Hope. Over five feverish days they turned lived experience into product roadmaps: blockchain receipts showing exactly where R2 donations land, WhatsApp bots that let a customer donate from a till slip, social-video platforms that feed families when viewers watch, and farm-to-community logistics that rescue “ugly” fruit and vegetables bound for landfill. The prize: the promise of co-development and seed funding of up to R1 million to pilot the winning solution.

This was not a demo day for novelty’s sake. Add Hope is no small civic lab experiment — it is one of South Africa’s largest private-sector feeding programmes: a 16-year project that combines voluntary R2 donations from customers with KFC’s own contributions, supports more than 3,300 feeding centres, and has helped provide millions of meals to children across the country. KFC and civic partners say the programme reaches well over 150,000 children and provides tens of millions of meals annually — a scale that makes the hackathon’s remit extremely practical: how do we make an already-huge system faster, more transparent and more scalable?

From lived experience to usable tech: the winners and their ideas

Judges awarded the top prize to a team of university students and young technologists now being reported as Cntrl-Alt-Del-Hunger (sometimes styled Ctrl-Alt-Del-Hunger). Their concept — reported as Misfits Mzansi in partner briefings — builds a digital marketplace and logistics stack that diverts cosmetically imperfect but nutritious produce from farms to food-insecure households and feeding centres. It combines last-mile routing, micro-payments and short-form edutainment: users earn small ad-driven donations simply by viewing cooking challenges and micro-lessons, directly linking engagement to meals served. The team’s plan won the judges’ backing and the potential R1m seed allocation to move from prototype to pilot.

Runner-ups also pointed the way forward. Streetwise Scripters sketched an integrated donor ecosystem — a real-time donation map, loyalty rewards that unlock free meals, and a TikTok-to-till storytelling funnel to keep donors emotionally invested. Bit Coders presented an inclusive chatbot and payment flow that uses mobile money rails so non-KFC customers can also give (and download tax receipts). Hack 4 Hope prototyped a QR-to-blockchain system that produces immutable proof of donation and “HopeCoins” that gamify repeat giving. Collectively, the projects illustrate a single idea: make giving simple, visible and social — and people will do more of it.

Why KFC opened the Add Hope blueprint — and why that matters

In a move that surprised some corporate-watchers, KFC Africa open-sourced the Add Hope blueprint at the hack — a decision framed as a deliberate shift from proprietary CSR to shared social infrastructure. The argument is strategic: when the mechanics of impact (how to recruit, train and support 3,300 feeding centres; how to route food; how to trace donations) are public, other organisations can replicate, adapt and scale what already works. KFC’s leaders and partners argued that collaboration — not secrecy — will expand reach faster.

Andra Nel, KFC Africa’s Head of Brand Purpose and ESG, captured the spirit bluntly: Gen Z “understand hunger because many have lived it and they understand technology because they were born into it” — a combination she called a “sweet spot for innovation with purpose.” That mix of lived experience and fluency with AI, mobile money and social platforms is what made ideas practical rather than purely theoretical.

The technology playbook: transparency, inclusion and behavioural design

The hack revealed three recurring technical themes that could reshape how food assistance is delivered in South Africa:

-

Transparency at scale. Blockchain-style proofs and QR traceability give donors verifiable assurance that money becomes a plate, a bag of veg, or a school snack — a powerful trust mechanic when small donations must prove impact to scale.

-

Payment and accessibility. Integrations with mobile money (MTN MoMo), card rails, and QR-enabled till-slips make giving inclusive — essential in a country where many citizens are unbanked or under-banked.

-

Gamified social engagement. Short video, loyalty rewards and “watch-to-give” mechanics turn passive scrolling into philanthropic impact — and create recurring donor behaviour rather than one-off impulses.

Those three ingredients — believable proof, multiple simple payment paths, and repeatable social experiences — are what judges said would make a seed investment worth taking forward into pilots with KFC’s partner network.

A coalition of corporates, civil society and academia

The Biggest Hunger Hack wasn’t just a Samsung-style innovation theatre. It was co-designed and witnessed by a coalition: University of Johannesburg (the host), impact NGOs such as Gift of the Givers, funders and corporate supply-chain partners. KFC announced new collaborations with companies including McCormick, Tiger Brands, Foodserv, CBH, Nature’s Garden, Digistics and Coca-Cola Beverages South Africa — partners whose logistical capacity and product streams could make rescued produce and bulk donations movable and nutritious at scale. Judges and speakers also flagged the broader economics: stunting and malnutrition are not only moral failures but economic drains on GDP, and interventions must therefore be both humane and efficient.

Scale, funding and measurable outcomes

Add Hope’s scale matters because it changes the calculus of pilot design. KFC says Add Hope has channelled more than R1 billion into feeding efforts over its lifetime (a mix of public and corporate contributions), and delivers tens of millions of meals annually. That infrastructure — 3,300+ feeding centres and a national distribution footprint — is a rare resource: pilots are not starting from scratch but can test within an existing, national network. That makes R1m seed funding catalytic if it produces systems that scale across those centres.

Critically, the project’s success will be judged not on elegant code but on measurable impact: increases in meals served, reductions in food waste, faster fund-to-plate time, reduced leakage and demonstrable improvements in child nutrition and school attendance. The next months will be about translating prototypes into monitoring frameworks and data pipelines that can answer those questions.

What this means for South Africa — and why Gen Z matters

South Africa’s food insecurity is structural: household incomes, unemployment, and distribution failures create recurring shortfalls for millions of children. Tech does not substitute for social policy, jobs or agricultural reform. But it can tighten the supply chain, expose waste, build donor trust and create frictionless ways for ordinary citizens to give in ways that are visible and repeatable.

That is precisely the contribution Gen Z brought to the room: systems thinking plus lived urgency. “They were born into technology and many have lived hunger,” Andra Nel said — and that combination matters when solutions must be rapid, culturally fluent and scalable.

Pilots, partners and the National Convention

KFC and partners say the immediate next step is co-development: moving the best ideas into pilots across select feeding centres with partner support, and reporting outcomes ahead of a National Convention on Child Hunger slated for early 2026. If pilots hit targets, the hope is to replicate successful modules across all 3,300+ Add Hope sites and to export the open-source blueprint internationally. The prize money is headline news; the real work will be in governance, accountability and long-term funding for interventions that prove they move metrics for nutrition and learning.

A different kind of charity, a new kind of citizenship

The Biggest Hunger Hack is part symbolic, part practical. It is a ceremony of civic imagination — a ritual in which young people convert frustration into product — but it is also a test of a deeper claim: that the private sector can show how to scale social programmes, and that it can do so in the open.

If Misfits Mzansi and its fellow teams can turn prototypes into repeatable, expandable systems, the hack will be remembered not for R1m but for the way it rewired the relationship between charity and technology: making small donations traceable, turning entertainment into meals, and rescuing food that would otherwise rot into dignity for children at tables across South Africa.

That is the measure of success here: devices and apps that don’t merely impress judges, but that stack up, site by site, into fewer hungry mornings for a generation still trying to grow into itself.